Chapters of the exhibition »Vija Celmins | Gerhard Richter. Double Vision«

The artists

Born in Riga, Vija Celmins immigrated as a child via Germany to the United States, where she began her career as an artist in Los Angeles, California in the 1960s. She has lived in New York since the early 1980s. Celmins sees her artistic work as a form of translation (“re-description”) from one surface to another – either by looking directly at objects or on the basis of photographs. Her works are subtle, quiet, and marked by an attention to detail, relying entirely on calm and careful observation in both the making and viewing of art.

Gerhard Richter shares experiences of war and migration with Vija Celmins. He was born in Dresden and emigrated from East Germany to Düsseldorf (in West Germany) in 1961, where he studied at the local art academy and later worked as a professor. Gerhard Richter’s extensive artistic oeuvre, which is characterized by a vast richness of variation and an impressive range of styles, consistently and persistently revolves around fundamental questions of seeing and representation, much like that of

Everyday Objects

Both Vija Celmins and Gerhard Richter consider their paintings of everyday objects from the early 1960s to mark the real beginning of their artistic careers. They discovered their pictorial motifs in their immediate surroundings: A lamp, a radiant heater, or a hot plate from Celmins’ studio in Los Angeles, as well as a kitchen chair and a curtain from Richter’s Düsseldorf apartment were elevated to art through the act of painting them. Richter’s paintings from that period were already based on photographic originals, photos that he had either taken himself or found in newspapers and magazines. By painting the things they could see, both artists were able to approach these things directly and to train their gazes. Their artistic beginnings were characterized by the desire to be as unencumbered as possible by theory and overblown interpretations.

Disasters

Vija Celmins’ and Gerhard Richter’s biographies link their early experiences with the horrors of the Second World War. Destruction, violence, and flight shaped their childhoods and adolescence. In 1944, Celmins fled with her family from her native Latvian city of Riga to the United States via wartorn Germany. Richter experienced the devastating bombing of Dresden in February 1945 from the nearby countryside. Prompted by media images of contemporary conflicts in the 1960s, both Celmins and Richter came to terms artistically with their traumatic childhood experiences. Black-and-white newspaper photographs of military aircraft, warships, and burning houses served as templates. The gray color of these images seems to cast the drama of the subjects in a timeless state of suspension, blurring the boundaries between past and present. At the same time, the photographic originals create a distance from the depicted scenes – they are, after all, second-hand memories or documentary images. This distance offered both artists an opportunity to concentrate entirely on the processes of painting and reappraisal.

A Window on the World

In the early Renaissance, the idea of a painting as a window to the world became established in Europe. This was accompanied by the desire to capture the three-dimensional reality of the external world as illusionistically as possible on the two-dimensional surface of the canvas. Vija Celmins and Gerhard Richter address this principle in their artworks – but not without reflecting on and expanding it from a contemporary perspective. Richter, for example, takes the early modern idea literally and has us look through four panes of glass. The iron construction that encloses these glass panes provides a frame as in a panel painting. But the content of the picture is no longer predefined, and what we see depends on our point of view and the surrounding environment. Celmins’ prints also resemble small windows, revealing very different scenes: Star-filled night skies, an airplane, and a detailed depiction of a work by Marcel Duchamp. Seemingly disjointed, these views stand side by side, challenging us to simultaneously let our gazes wander off into the distance and to focus on each small detail.

Seascapes

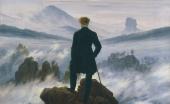

Depictions of the sea play an equally important role in the oeuvres of Vija Celmins and Gerhard Richter. More than almost any other motif, the endless expanse of the sea’s moving surface lends itself to exploring the possibilities and limits of illusionism and the power of drawing and painting. There is a long tradition of these so-called seascapes in European landscape painting. But Celmins’ and Richter’s seascapes evade both the idyllic so-called pastoral landscape scenes, which have depicted shepherds and grazing cattle since the 17th century, and the immediacy of 19th -century plein air painting. Their paintings may seem realistic, but they are deliberately constructed. Celmins’ drawings and paintings of the ocean’s surface are based on her own photographs, which she repeatedly transferred to canvas or paper using various materials over long periods of time. Richter’s sea and sky paintings are based on various vacation photographs taken by the artist, which he later arranged into compositions. The structures of waves and clouds seem to merge into each other, to mirror each other, and to provoke the question: What do we really see?

The Color Gray

Throughout the course of his artistic career, there is no theme that Gerhard Richter has devoted himself to with the intensity and richness of variation with which he has explored the color gray. Even the early object paintings, the chairs, tables, and curtains, which were created on the basis of black-and-white photographs, are predominantly painted in shades of gray. His first gray monochrome paintings date from the 1960s and are part of Richter’s so-called color chart paintings. In these works, the color appears as a readymade, as a found and adopted material to which no emotional or illusionistic qualities are attached. Other purely gray panels are the result of early overpaintings, in which Richter painted over his own work. What was initially intended as a gesture of destruction was developed by the artist into his own pictorial language in the 1970s. The color gray became a creative element that Richter repeatedly presented in new ways, through countless variations in color application and the use of different painting supports and tools, without ever submitting to a single interpretation. Vija Celmins’ artistic work is also characterized by a reduction of color in favor of the nuances to be found within the color gray. However, unlike Gerhard Richter, Celmins has consciously refrained from pursuing pure abstraction in her work.

Mirrors and Doppelgangers

What is the relationship between images and reality? Time and again, the works of Vija Celmins and Gerhard Richter revolve around this central question. Using different strategies, their artworks challenge our perceptions and, at the same time, test seeing as a means of cognition. To do this, Celmins works with the strategy of doubling. Over a period of several years, she created bronze casts of stones she had collected, exhibiting these copies alongside the “originals”. The casts are so meticulously painted that found and made objects are almost indistinguishable to the naked eye. Mirror images are also based on the phenomenon of doubling. Mirrors in different variations and sizes are found within Richter’s work. While the mirror works composed of glass that Richter coated with colored paint are still reminiscent of paintings, the industrially produced versions initially appear to be less artistic; the way they are produced denies any individual input, any representation of reality. Through the use of mirrors, Richter highlights the inability of capturing reality itself, instead always portraying an illusion of reality.

Back to the Tools

With their works, Vija Celmins and Gerhard Richter knowingly address their own artistic craft and the traditions associated with it. In the period between 1965 and 1966, Richter painted several small-format paintings of two overlapping sheets of paper. The lower right corner of the upper sheet is curled up. This gives the impression that the paper is curving – an optical illusion known in art history as trompe l'oeil, the roots of which go back to antiquity. Celmins also makes use of this artistic strategy. Her illusionistic, painted wooden sculptures of erasers, pencils, and chalkboards appear deceptively real. At the same time, the exaggerated size of the objects undermines the illusion. Celmins' works deceive our eyes while simultaneously drawing attention to the attempted deception. As a result, this tongue-in-cheek engagement with reality and truth opens up an exciting dialogue that spans artistic genres and art historical eras.

Near and Far

Vija Celmins created her first depictions of the starry night sky in the 1970s, and the subject has been part of her work ever since. Her prints, drawings, and paintings seem to be amazingly close to reality and yet also completely abstract. It almost feels as if the infinity of the universe has been rendered tangibly in front of our eyes. However, if one gets close to the small-format pictures, the illusion gives way to the materiality of the canvas or the printed paper: The surface of the painting remains impenetrable and can’t hide its two-dimensionality. The distinctive realism of Celmins’ works turns out to be twofold, encompassing both the subject depicted and the process of its creation. The depictions of the night sky are based on photographs of satellite images that Celmins found in scientific magazines. If one looks more closely, her prints and paintings address this moment of mediatedness: Celmins has meticulously incorporated traces of the photographic production process used for her templates or referenced photographic negatives by reversing the brightness values within her artworks. We can therefore conclude that seeing, like any artistic practice, is a constructed process that challenges our eyes, our mind, and our imagination